Written by Greg Bullock

First published on November 15, 2017; last updated September 8, 2019

Have you ever experienced recurring vertigo as part of a migraine attack? If the answer is frequently yes, you may be dealing with a very specific subtype of the headache disorder known as vestibular migraine. It has also been previously labeled 'migraine-associated vertigo' and 'migrainous vertigo' in clinical literature, although vestibular migraine more accurately encompasses other symptoms such as nausea, lightheadedness and balance instability. But regardless of how researchers and doctors describe it, vestibular migraine is a very real and often disrupting diagnosis for patients.

Contents

I. History, definition and diagnosis

II. Signs and symptoms

IIa. Vertigo and other vestibular symptoms

IIb. Migraine-related symptoms

IIc. Emotional symptoms

IId. Migraine with brainstem aura and Meniere's disease

III. Triggers

IV. Prognosis and impact

V. Treatment

VI. Resources

Vestibular migraine: history, definition and diagnosis

You might be surprised to learn that “vestibular migraine” is a relatively recent diagnostic term, describing the vertigo, dizziness and disequilibrium symptoms that are caused by migraine. In fact, it was not until 2013 that vestibular migraine was added to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), with the following criteria proposed for diagnosis:

- Moderate to severe vestibular symptoms (notably vertigo) during at least 5 separate attacks, which persist for 5 minutes to 72 hours

- A prior history of migraine with or without aura

- At least half of all migraine attacks have one of the following:

- Presenting headache that is moderate or severe; concentrated in a singular location; characterized by pulsating pain; or aggravated by physical activity.

- Painful sensitivity to light (photophobia) and/or sound sensitivity (phonophobia)

- Visual aura (e.g. floaters, zig zags, negative aura, blind spots, etc.)

These advancements in the clinical definition of vestibular migraine were shaped by decades of study on the causal link between vertigo, dizziness and migraine—often labeling it as migraine-associated vertigo (MAV) or migrainous vertigo. Many studies have since identified migraine as one of the leading causes of vestibular symptoms (along with Meniere’s disease), with an estimated global prevalence of 1 percent having vestibular migraine. However, the actual number of patients who experience vertigo during migraine attacks may actually be much higher.1

According to one study, 30% to 50% of all people with migraine experience vertigo, balance issues or dizziness as part of some of their attacks. Although only one in four patients actually met the clinical diagnosis for vestibular migraine, these findings suggests its high prevalence among people who already have migraine. Even among those with general vertigo, migraine may be an underlying cause or comorbidity in as many as 10% of patients.2-3

Vestibular migraine is also more likely to be diagnosed among women, particularly those between the ages of 30 years and 50 years, although it can develop at any age. Amazingly, patients may have migraine for more than a decade before ever experiencing vertigo or vestibular migraine, and there is further evidence that episodic symptoms early on in life and/or a family history of migraine may be leading indicators of the onset of vestibular migraine.17 Some studies have also suggested that vestibular attacks may correlate specifically with migraine with aura, but more analysis is needed to verify that connection.4

In addition, researchers have looked at the underlying pathophysiology between migraine and vertigo. In the early 1990s, it was discovered that dizziness and vertigo were more prominent during the headache or attack phase of a migraine. They hypothesized that there was dysfunction in neuronal communication within the vestibular system, thus causing the longer-lasting symptoms described by patients. In addition, they also made an important distinction between vestibular issues that were shorter in duration and often experienced during the aura phase. They believed these to be more typical of general migraine process than specifically migraine-associated vertigo. It is one of the main reasons why vestibular symptoms that occur during migraine aura is not immediately considered vestibular migraine.5

Signs and symptoms

Did you know that approximately 60% percent of patients with migraine-associated vestibulopathy have attacks which last several minutes to several hours, with nearly one-third even experiencing attacks that continue for several days?2 That can be pretty scary, and the pain and discomfort is not restricted to just vertigo. In fact, there are dozens of corresponding symptoms that may or may not be unique to vestibular migraine. We take a closer look at the experiences and feelings that can happen during an episode.

Svea Ellen describes some of the vestibular migraine symptoms that she deals with as part of her vestibular migraines.

Vertigo and other vestibular symptoms

Ongoing vertigo is the hallmark of vestibular migraine, but there are multiple types of vertigo that can manifest. These include:

a) spontaneous vertigo, characterized by a false sense of self-motion OR a spinning environment

b) positional vertigo, which stems from shifting of the head to a different position

c) visually-induced or visual vertigo that is triggered by complex moving stimuli

d) head motion-induced vertigo, which occurs during the actual movement of the head

e) head motion-induced dizziness with nausea

Generally, spontaneous rotational vertigo and head motion intolerance were most frequently reported by patients with vestibular migraine attacks.1,3,6 In addition, the average duration of vestibular migraine vertigo is 3 hours and typically lasts longer on so-called “headache days”—although it can occur prior to attacks and during symptom-free periods as well.6 And no matter how it is experienced, it is no fun for a person who has to deal with these problems. Take Jamie for instance who described her vestibular migraine symptoms like this:

"I instantly become dizzy, get tunnel vision, basically cannot see what is in front of me, my cognitive processes slow way down, and I get many other neurological and vestibular symptoms. This has rendered it impossible for me to spend much time in stores at all. As a style blogger, I am invited to events, spend time in airports (vestibular hell), and I like to shop (hello, I do a style blog). Hence, this makes normally fun activities quite stressful for me."

Some describe the dizzy sensation as though the ground moves beneath their feet or the feeling of constant rocking or swaying such as would be caused by an earthquake or boat.7 Others have shared the damaging physical consequences the headache disorder has had on their their daily lives. Jillian shared this recently:

"I get up for school at 5:45 a.m., and when I am extremely dizzy and nauseous, it is sometimes too difficult to get out of bed. However, I do so and do my morning routine and then head off for school. When I am in class I try extremely hard to focus, but it is hard to when the room is tilting back and forth and spinning around you or you’re just experiencing the other feelings of dizziness which is too difficult to put into words. Walking the hallway is sometimes a nightmare; watching people continuously going by you – triggering your dizziness when you are already dizzy – is the worst. This causes me to either cut people off or walk straight into people, and on the inside I hope they won’t shout at me." (via The Mighty)

Beyond vertigo and general dizziness, there are countless other vestibular symptoms that can appear. Some of the most common include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Motion sickness or sensitivity

- Lightheadedness

- Tinnitus or ringing in the ears

- Inability to maintain balance or posture

Researchers have also identified a set of possible vestibular indicators that can occur outside of attacks—which may help in diagnosing vestibular migraine. Most of them manifest in eye-related issues such as dysfunction in tracking objects in motion as well as shifting focus from one object to another. Additionally, different forms of nystagmus—which is characterized by uncontrollable eye movements—are also more prominent.8

Additional migraine-related symptoms

As noted previously, there are a multitude of other migraine symptoms that can present with vestibular migraine. And these will often vary from attack to attack and between people with migraine. In fact, two of these symptoms—sensitivity to light and sound—are often necessary for accurate diagnosis of migraine-associated vertigo, with estimates showing that 60% of attacks are accompanied by these issues. Furthermore, other sensory sensitivities to touch and/or smell have also been observed at higher rates for those with vestibular migraine. Surprisingly, nearly one-third of all vestibular attacks do not include any headache or head pain, and there are even a minority of patients who acknowledge that their headache and vertigo occur independently of one another. This further reinforces the need to identify these auxiliary migraine symptoms in order to properly diagnose a patient.3, 8

Emotional symptoms and comorbidities

We have only discussed the physical symptoms that occur with vestibular migraine, but there are also emotional consequences as well. Specifically, there has been a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, as well reduced quality of sleep observed among those with migraine-associated vertigo.8 It is important to note that migraine and other headache disorders have long been connected with these emotional side effects, so there is no clear causal link. However, it does appear that these issues may be more severe even when compared with the general migraine population.

Migraine with brainstem aura (basilar migraine) and Meniere’s disease

It should not shock you to learn that vertigo and dizziness is not unique to vestibular migraine, although it is one of the most common underlying conditions that causes it. Migraine with brainstem aura (previously known as basilar migraine) and Meniere’s disease are two other conditions that present similar symptoms but also have key differences as well.

Migraine with brainstem aura has vertigo as its primary symptom, but it also typically includes ringing in the ears (tinnitus) and other auditory issues, speech dysfunction (e.g. slurring), and double vision. In addition, these symptoms are shorter in duration, between 5-60 minutes, most commonly occur during the aura or pre-attack stage of a migraine, and almost always are followed by headache.

On the other hand, Meniere’s disease is a disorder of the inner ear that results in vertigo and other vestibular symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Tinnitus, hearing loss, and congestion of the ear are also common for this condition and key signs for diagnosis. One of the main diagnostic impediments for medical professionals is that Meniere’s disease can present with headache in as many as 40% of patients, meaning they often have to look for other migraine-related indicators (e.g. photophobia, aura, anxiety, etc.) during examination.

Triggers

There is not necessarily a unique set of triggers for vestibular migraine, and—as with many migraine triggers—they often vary from person to person and between attacks. That said, specific triggers that precede vestibular episodes might be attributable to sudden or jerky motion, either of the body or head, rotational motion (such as by sudden turning of the head), or even riding in a car or flying on an airplane. Other research has also cited visually-disorienting environments as potential catalysts for vestibular attacks.

In addition, many vestibular migraine patients report more traditional triggers, such as:

- Food or dietary changes

- Caffeine use

- Exercise or physical activity

- Fluorescent lighting

- Sunlight or other bright light

- Stress

- Menstruation

It is vital to work with your doctor or headache specialist in order to identify the specific causes of your vestibular migraine attacks. Keeping a paper or electronic diary that records precipitating triggers is a great place to start and can allow you to better manage them—and hopefully prevent many attacks from happening in the first place.

Prognosis and impact

Vestibular migraine takes a significant toll on the physical, emotional and social well-being of patients. For instance, 87% of patients with migraine-associated vertigo still had disorienting vestibular symptoms after nine years—and nearly two-thirds rated the impact of their attacks as moderate or severe. Other analyses have shown that people with migraine who have vestibular symptoms have an increased number of headache days as well as a higher disability score and lower quality of life when compared with those who do not experience vertigo with their migraines.9-11 And as noted previously, emotional concerns such as anxiety and depression tend to be higher in those with vestibular migraine.

One of the main hypotheses for the severe impact of vestibular migraine relates to misdiagnosis. Researchers have identified that the majority of vestibular migraine patients often deal with their symptoms for at least one year prior to consulting with a doctor; and even then, as little as 20% of them are actually diagnosed with the neurological disorder.10,12 While not unusual for all types of migraine, overlapping symptoms with other conditions (e.g. Meniere’s disease and basilar migraine a.k.a. migraine with brainstem aura) can complicate the identification of vestibular migraine. In addition, as many with migraine-related vertigo may not have a corresponding headache, medical professionals often have to explore and rule out other possible causes of the vestibular dysfunction. Coupled with the fact that certain migraine prevention drugs list dizziness as a side effect, and the diagnostic waters can get pretty muddy.

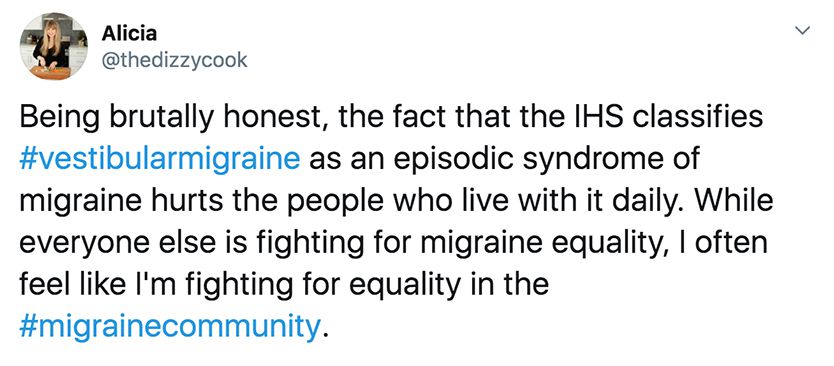

We also cannot discount the role that stigma may play in the diagnostic process. Although vestibular migraine is part of the international classification of headache disorders, it is considered an 'episodic syndrome' and not a primary headache disease. Furthermore, some within the medical community have been reluctant to adopt the term because of the high volume of shared symptoms with other vestibular conditions. And if the medical community cannot agree on how to define vestibular migraine, the direction of patient care may subsequently be impacted.

Along with leading patient and migraine advocates, we hope more conversation and research surrounding this disorder will bring improved clarity for everyone.

Treatment

There is no clear cut protocol for treating vestibular migraine, at least according to research. As a result, it often requires careful identification of symptoms and triggers, followed by a mix of medication, behavioral therapies and lifestyle changes. But the good news is that this combined and customized approach has helped as many as 92% of patients reduce their migraine-related vertigo and vestibular symptoms.13

Generally, triptans have been shown to be successful for migraine patients during the acute or attack phase, with a small clinical study showing above average success (versus placebo) for those with a vestibular component to their migraines. Additionally, over-the-counter analgesics—such as ibuprofen or aspirin—have also shown to be effective in addressing the onset of vestibular symptoms.14

Prevention or prophylactic medications include the following:14

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, nortriptyline)

- Beta blockers (e.g. propranolol)

- Calcium channel blockers (e.g. flunarizine)

- Antiepileptic agents (e.g. topiramate)

Lastly, general migraine-related lifestyle changes or natural treatments may be appropriate. Everything from dietary restrictions, specialty tinted migraine glasses (if fluorescents trigger vertigo, for instance), biofeedback and stress reduction techniques can be critical tools for vestibular migraine relief.

Resources for vestibular migraine

As we shared in the treatment section of this article, there is hope for people with vestibular migraine. And there is also a strong community of patients and advocates who want to help bring greater awareness to this condition. Below we have listed several organizations and online communities, which offer additional resources for vestibular migraine.

Vestibular Disorders Association

Neuro-Visual and Vestibular Disorders Center—John Hopkins Medicine Vestibular Migraine Professional (Facebook) Vestibular Migraine Community (Facebook) Vestibular Hope (Facebook) 1 Obermann M, Strupp M. Current Treatment Options in Vestibular Migraine. Frontiers in Neurology. 2014;5:257. doi:10.3389/fneur.2014.00257. 2 Stolte B, Holle D, Naegel S, Diener HC, Obermann M. Vestibular migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015 Mar;35(3):262-70. doi: 10.1177/0333102414535113. Epub 2014 May 20. 3 Strupp M, Brandt T. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vertigo and Dizziness. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2008;105(10):173-180. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0173. 4 Vuković V1, Plavec D, Galinović I, Lovrencić-Huzjan A, Budisić M, Demarin V. Prevalence of vertigo, dizziness, and migrainous vertigo in patients with migraine. Headache. 2007 Nov-Dec;47(10):1427-35. 5 Cutrer, F. M. and Baloh, R. W. (1992), Migraine-associated Dizziness. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 32: 300–304. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1992.hed3206300.x 6 Salhofer S, Lieba-Samal D, Freydl E, Bartl S, Wiest G, Wöber C. Migraine and vertigo--a prospective diary study. Cephalalgia. 2010 Jul;30(7):821-8. doi: 10.1177/0333102409360676. Epub 2010 Mar 12. 7 Vuralli D, Yildirim F, Akcali DT, Ilhan MN, Goksu N, Bolay H. Visual and postural motion-evoked dizziness symptoms are predominant in vestibular migraine patients [published online July 13, 2017]. Pain Medicine. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx182. 8 Dieterich M, Brandt T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? J Neurol. 1999 Oct;246(10):883-92. 9 Radtke A, von Brevern M, Neuhauser H, Hottenrott T, Lempert T. Vestibular migraine: long-term follow-up of clinical symptoms and vestibulo-cochlear findings. Neurology. 2012 Oct 9;79(15):1607-14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e264f. Epub 2012 Sep 26. 10 Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Feldmann M, Lezius F, Ziese T, Lempert T. Migrainous vertigo: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology. 2006 Sep 26;67(6):1028-33. 11 Akdal G, Baykan B, Ertaş M, Zarifoğlu M, Karli N, Saip S, Siva A. Population-based study of vestibular symptoms in migraineurs. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015 May;135(5):435-9. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.969382. Epub 2015 Feb 9. 12 Vitkovic J, Winoto A, Rance G, et al. Vestibular rehabilitation outcomes in patients with and without vestibular migraine. J Neurol 2013;260:3039–48. 13 Cha Y-H. Migraine-Associated Vertigo: Diagnosis and Treatment. Seminars in neurology. 2010;30(2):167-174. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1249225. 14 Tsang, B. K. T., Anwer, A., & Murdin, L. (2015). Diagnosis and management of vestibular migraine. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 22(10), 457-468. 15 Baier B, Winkenwerder E, Dieterich M. "Vestibular migraine": effects of prophylactic therapy with various drugs. A retrospective study. J Neurol. 2009 Mar;256(3):436-42. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0111-3. Epub 2009 Mar 6. 16 Sugaya N, Arai M, Goto F. Is the Headache in Patients with Vestibular Migraine Attenuated by Vestibular Rehabilitation? Frontiers in Neurology. 2017;8:124. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00124. 17 Teggi, R., Colombo, B., Albera, R., Asprella Libonati, G., Balzanelli, C., Batuecas Caletrio, A., Casani, A., Espinoza-Sanchez, J. M., Gamba, P., Lopez-Escamez, J. A., Lucisano, S., Mandalà, M., Neri, G., Nuti, D., Pecci, R., Russo, A., Martin-Sanz, E., Sanz, R., Tedeschi, G., Torelli, P., Vannucchi, P., Comi, G. and Bussi, M. (2017), Clinical Features, Familial History, and Migraine Precursors in Patients With Definite Vestibular Migraine: The VM-Phenotypes Projects. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. doi:10.1111/head.13240.

Research references